Follow along on my Angolan Medical Mission

Read moreImpossible Decisions

A 5-year-old boy presents with exquisite abdominal tenderness and ten-day history of fever with seizures. The clinical picture points toward cerebral malaria with typhoid, a surgical emergency when accompanied by vomiting or ruptured bowel. Cavango is not a surgical clinic, however, removing ulcerated ileum requires air evacuation to Lubango and consult at CEML. Families are billed for these expenses, but rarely pay them, meaning the mission must make the critical decision of whether or not to spend the money. To say finances are tight here would be a gross understatement, spending must be done with precision and prejudice.

This child appeared gravely ill but did not fit the criteria for evacuation. Spending the money now would mean not having it later for a potentially more critical patient. To complicate things, his 8-month-old sister is malaria positive and had the same history of fever and seizures. Red-orange hair (indicating malnutrition) and profound anemia (estimated at a hemoglobin of 4 based on conjunctival pallor) made this child the greatest concern in the clinic (and most likely to be evacuated). These siblings were just the first of many that day, heralding the beginning of malaria season.

After much vacillation, it was decided we simply could not allocate mission resources to activate MAF when the child was able to keep down soro (water with hydration salts). We left the clinic with trepidation, telling staff to send for us if the child began to vomit. Hours passed and night turned to morning. As I poured my coffee, channel 08 on the CB radio crackled to life with matter-of-fact Portuguese: the anemic child we were most worried about had made it through, her big brother hadn't.

The parents came to us as a last resort, the decision wasn't easy for them. They had consulted their elders and gone to three other clinics before making the 200 km motorbike trip to Cavango. They asked for help, expecting us to heal their sick child. We treated with antibiotics and the tincture of time, beyond that the situation was in God's hands. Later we would find out this family had lost another child to pestilence earlier this year; their third will likely follow soon. What was lost was not only a child’s life, but trust in western medicine, and in our clinic’s relationship with the community. Post-mortem review of the case pointed to the right decision being made; death did not result from a lack of surgery, death occurred due to typhoid fever, but that was little comfort in the face of such an outcome.

Inpatients here have bunks assigned to them in a concrete building, but few stay there. Those without TB who are able to ambulate generally stay in the jangos (traditional meeting huts erected around the property). As at CEML, patients rely on family members to prepare their meals, meaning the huts are perpetually fuming smoke through their thatched roofs. Normally ebullient, regardless of physical conditions, the patient huts fell silent as the tiny body was carried out to the ambulance.

Her last living child in her arms, the mother follows the procession out of the clinic and collapses on the ground in absolute lament. A supportive crowd gathers around her as the departed is driven off to their home village. The youngest is far too critical to return home or to be without a nursemaid for long. The poor mother is left with the impossible decision to stay behind, alone, as the boy is interred; likely to relive this nightmare sooner than any of us can conceive.

We made it through the day and treated everyone both inpatient and out. With Dr. Tim still recovering from his malaria, and showing new symptoms myself, we retired home to finish meetings at the Kubacki jango there. Several minutes into a conversation about rebuilding the water lines to the clinic a frantic father bursts in crying that his child is dying. We had seen the child earlier today, a 15-month-old malaria patient who had been able to keep down his medications and had no overt signs of concern. Without warning the malaria precipitated acute respiratory distress syndrome. By the time we made it back to the clinic he had gone into respiratory arrest and passed.

Earlier in the day I had felt so close to the inpatients at the mission. I felt accepted, like the patients knew I was there for them as an equal. After the second loss of the day we piled into our lifted 4x4 to motor back to our safe ranch home full of electric appliances. A tormented mother hoisted the lifeless body of her son onto her back and secured him with a pano, his little hands no longer holding on for security. We passed glaring eyes filled with mistrust and I melted back into my seat. Equal? Not even close.

My Friend the Witch Doctor Taught Me What to Do

Sitting at home in suburbia watching movies about the old world, I always romanticized the role of the witch doctor. Without squabbling over power or wealth, they were a community leader, a trusted advisor, someone who could expel demons and create wellness potions out of plants the western world hadn’t even discovered yet. When I began to travel, bush medicine gained an association with mind altering psychotropics used in spiritual rites like the peyote buttons of Native Americans, ayahuasca of the Incas, or muscarinic Fly Agaric mushrooms of Siberia. This essay is not meant to argue for or against these concoctions, simply to illustrate the informed, controlled manner in which these medicine men practiced. Tribal diviners were attributed with knowledge, wisdom, vision, and benevolence. How disappointing, then, to find nothing could be further from the truth here in Angola.

Quite literally from the very first patient, my preconceptions of bush medicine started to falter. Coming to CEML for help is often the last resort for villagers. Western medicine is considered unsavory, an aface to traditional medicine which is the mainstay of the entire community. When someone complains of chronic abdominal pain, western doctors develop a differential diagnosis to identify the most likely (and the most deadly) illness(es); this would then inform indications for testing and treatment. In the bush, chronic pain is treated by nicking the skin over the affected area. This can be done for blood letting to rid the victim of corporeal spirits or curses, or the wounds can be rubbed with poison which causes severe inflammation and pustulence. In tribal tradition, medicine must hurt to work; for this reason, we do not put lidocaine in our joint injections.

When the superficial cuts fail to produce results, the witch doctor has no choice but to escalate his next salvo: a bolus of boiled poison administered as an enema or injection. Dr. Tim details a period at CEML when one patient a day would arrive icteric (having yellow eyes, indicates liver failure), obtunded, or comatosed. Within 48 hours the patient would perish from fulminant hepatitis. The cause is now well known to western practitioners in Angola to be traditional medicine. In all the years since patients began to admit this, however, they have yet to disclose what they were prescribed by their esteemed advisor; no antidote, therefore, has been discovered. At the time of writing this I have two patients under my care who will soon perish from this very torment. They never complain though, never blame the witch doctor, never get angry, they accept their fate as God’s will and ask you to make them comfortable (a relative term out here).

Norm and Audrey Henderson have been instrumental in building an Anglican church on the outskirts of Lubango. A group that once met in the shade of a pair of eucalyptus trees grew and grew until it was clear they would need a home for the parish. In the common area of a swath of Nyanekan homesteads, community members donated their sweat equity and various skills to build the church out of the very earth on which it was situated. Bricks of mud, benches of local timber, and doors of salvaged corrugated steel came together to create something greater than the sum of their parts. The clarity of song this simple building creates boggles the mind, even for a relatively small group which gathered on my first Sunday with the congregation. It would be unusual to begin any formal program at its scheduled time, but on this particular day it took worshippers longer than usual to arrive. Audrey fills the time changing wound dressings for parishioners outside the church. Before the pastor even began his welcoming remarks, Norm and Audrey knew something was amiss.

Nurse Audrey Henderson

Changing Dressings Before and After Church service

A neighboring village had experienced a tragic loss several days prior, a young infant had succumbed to his respiratory infection. Audrey knew this child. She had treated him. He was sick, but not gravely so; what happened? We traveled to the community after church to grieve with the family. A young couple in visible shock sat slumped on a handwoven blanket in the shade of an adobe hut. Elder women in traditional panos (lengths of batik cloth worn as skirts, head-dresses, or child slings) encircle the couple in the courtyard of the village as young men bring us chairs from their homes. Norm offers the bereaved parents a prayer of solace in Portuguese which is translated to Nyaneka. Slowly an uncle, friends, and neighbors begin painting a picture of what happened which requires a great deal of distillation to clarify.

Not completely trusting Audrey’s antibiotics and symptom management, the parents consulted with the local witch doctor. A common staple here is flour with various amounts of water and heat. A little water and lots of flour makes “funge,” a filling, tasteless goo that sits like a rock in the stomach. A little flour and lots of water makes “kissangua,” a meal replacement that can be packed in a used plastic bottle for long days at church or waiting in line at the clinic. For some reason, this particular witch doctor felt the appropriate treatment for this child’s respiratory infection was flour with no water, placed directly in the mouth. He was asphyxiated. The infant was killed by an untrained, over-confident charlatan who would be convicted of murder in the United States. Here, though, the infant was simply considered too far gone to be saved, likely the victim of a curse set upon the family by an enemy in another village.

After excusing ourselves from the somber, but somehow beautiful ceremony we felt very privileged to be a part of, we were immediately ushered to another homestead plaza not 50 meters away. Here a man was accused of this very act, of cursing a child who died in a distant village (a child he had never met), and had thus been beaten until nearly dead. Audrey had been present and chased the men off before they could finish the job. Now the man was complaining of severe chest pain and difficulty breathing, likely from broken ribs. It had been several weeks now since the assault and I was able to rule out a lung or splenic laceration, so we delivered the unsatisfying news that he just had to wait for the ribs to heal. Thinking we were finished, we turned to leave when several other villagers began to approach us with various concerns, not the least of which was wanting to be freed from the grip of alcohol (Sunday is drinking day, usually on homemade hooch). Norm made a quick escape to the Hilux claiming he was not medically trained, I followed after as Nyaneka is not one of my languages, Audrey, however, has an above average capacity for compassion and stayed well after until Norm began honking the horn to clear off other would-be traditional-to-western-medicine converts.

We beat a quick retreat back to asphalt. I lamented the demise of my romantic notions of bush medicine.

Dormiste Bem? (How did you sleep?)

It would be quite silly of me to think the clinic here would function like my home hospital in Toledo; in fact, the whole reason I came here was to step outside my comfort level and see how austere medicine is practiced on the ground. Nothing, however, could have prepared me for what awaited my arrival at CEML.

Fighting through morning gridlock caused by lines at the petrol station, we meander through Lubango, up into the hills toward “Cristo Rei,” a replica of Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro. Three kilometers before the statue, we turn off onto a short dirt road which will deliver us to CEML. The grassy margin of the road is abustle with villagers waking from their slumber under trees and preparing meals over campfires. The clinic cannot afford to feed its inpatients, so families must travel with their loved ones to prepare their meals, feed them, and bath them. Often the portions heap in an almost comically mounded mass that seems impossible to consume in a single sitting. But consume they do, not for gluttony sake, however, quite the opposite. Patients and hospital staff often do not know when their next meal will come, so in times of plenty they pack in as much as they can in anticipation for times of scarcity.

The smell of the campfires follows us to the porticoed waiting area which is already full of new patients. Many traveled for days to get here and spent the night under the stars waiting for the gaggle of whitecoats to arrive in the morning. Though CEML is more a compound than a free-standing clinic, it is still quite small in comparison to the grand scale hospitals in town. Central Hospital, the Maternity Hospital, and the Children’s Hospital are all monolithic castles which loom over downtown Lubango like benevolent guardians. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth. Relics of Angola’s ties to the communist empire, some facilities were built by China, others by Russia, and all are staffed by Cuban physicians who may, or may not, have wanted to come here. Infamous for refusing to integrate into Angolan culture, the Cubans speak a broken Span-uguese creole, take jobs from Angolan trained residents who go unemployed, and stopped developing their clinical thinking after medical school.

Often patients at these “hospitals” are victims of unspeakable horrors: surgeries by grossly unqualified practitioners, prescriptions of drugs with obvious interactions (or simply the wrong drugs for the condition), and an HIV department which only accepts 20 patients per day, so faculty can leave by 11am. Curiously, when these physicians leave, so too do the drugs used to treat HIV. Doctor Kubacki, the man who brought me to this country, comes to Lubango from his extremely remote clinic in Cavango once a month or so to procure meds. Outside the central pharmacy lurk the most unlikely drug dealers: men who speak in hushed tones offering quartan (malaria treatment), rifampin, or isoniazid (tuberculosis medications). Inside, the pharmacy is perennially short of supply (even when the drugs are clearly visible on the shelves). The pharmacists could be keeping the drugs for their own relations, for times of higher demand when they can raise prices, they may not want to give their drugs to the rural poor, or they could just not be in the mood to count pills.

The Angolan government does not permit direct import of medical supplies from Namibia or the United States, which leaves clinicians precious few options to stock their shelves. Buying from the blackmarket scalpers outside the pharmacy will just perpetuate their fraud, so this is an absolute last resort. Local grocery store pharmacies must retire expired drugs, even though a military study of 20-year-old drugs found no loss of efficacy, or adverse effects, from all but aspirin or tetracycline respectively. Therefore, these expired meds are stockpiled by many physicians who practice in frontier clinics. But my favorite method? Smuggling. In a very “Robin Hood” reverse crime model, doctors have taken to road-tripping down to Namibia, buying drugs in bulk, and bootlegging them back across the border hidden within their 4x4s.

When the federal healthcare option offers poorly trained physicians, whose biggest concern is going home before lunch, and may or may not have access to medication, it’s easy to see why private clinics such as CEML are the preferred option. That does not mean to say we are the paragon of medical advancement. We do not have an x-ray, our lab is extremely limited, surgical instruments may have come from the hardware store (or be disposables that have been sanitized for reuse), scrub sponges that should be thrown away after one use are replaced weekly at best, and the pharmacy often stocks only one (often out-moded) drug from any given class. Anaesthesia for surgeries is similarly archaic with only local anaesthesia, or spinal block, in most cases (including open abdominal surgery). When this doesn’t take (or if the nurse missed the nerve), ketamine can put the patient in a dissociative state and help them forget the agony.

A common procedure here, in fact a specialty for which we are highly sought, is obstetric fistula repair. I knew coming here would expose me to things I could have never imagined, this is one of them. Nurse Audrey Henderson, my host-mother here in Lubango, directs the CEML fistula program and cares for all of the fistula women. She has gone so far as to develop a permanent encampment for the women just a hundred yards from the hospital, not only so they can receive immediate care if necessary, but so they can have their own sense of community and belonging. Audrey told me that the patients here are almost always abandoned by their “husbands,” a cruel practice that required explanation.

Obstetric fistulas happen when labor fails. In a developed nation we would rush a woman into the OR for a cesarean, but that is rarely available here; in a remote village, there is little that can be done. A witch doctor may concoct a tea with similar properties to oxytocin to promote further, harder contractions. The problem is rarely a lack of effort on the mother’s part, however, it is more likely to be incompatible anatomy (often because the mother is too young, and her hips too under-developed, to accommodate child birth). When the fetus is contracted against a birth canal which is physically incapable of expanding, delivery ceases, the fetus perishes, and the reproductive tissues are compressed so hard they cannot be perfused. Inevitably this causes tissue death, necrosis, and the formation of a fistula (a non-anatomic hole which opens between the vagina and either the bladder, rectum, or both).

Not only does the poor mother then smell of rotting flesh, but she is now incontinent of stool and urine and truly cannot stay clean. Even if a husband could cope with this, his young wife is also now infertile and will not bare him any children; for most this is too much to take and they will leave to find a new bride. Rejected and alone, these women find new hope after receiving a surgical closure of their fistulas and in Audrey’s special patient village. In fact, they celebrate and sing together, casting off the darkness of their old lives, and accepting a new life together. They invited Dr. Haniel and I as special male guests; I’m glad he was there to translate for me or I would have been lost.

I guess I’m gonna have to pick up some Portuguese. Let’s start simple with the traditional Angolan greeting: dormiste bem?

"Welcome to Africa! Welcome to My Country!"

As we dip below the cloud line, I get my first glimpse of what will be my new host country for the coming months. What first catches the eye is the inverted color scheme from Angola’s southern neighbor Namibia: a russet expanse pocked by occasional scrub brush yields to verdant jungles scarred by clay-colored tracks and trails with only occasional farm lands cleared for cattle. It is surprising, then, the (near) absence of wildlife; the result of unregulated trade in bush meat which is still available in restaurants today.

After a couple hours of scrutiny from the local immigration authorities, my passport received a shiny new visa and I was allowed to go meet the Kubackis who have patiently been awaiting my arrival outside. Dr. Tim and Betsy Kubacki together operate the Cavango Mission Station, an outpost of Centro Evangélica de Medicina do Lubango (CEML) 500 Km away where I will be working in a couple weeks. For now, though, they drive me into town to meet my host family in Lubango, Norm and Audrey Henderson of Ottawa, Ontario. Both couples serve as Anglican missionaries who were brought to this country by the Fosters.

No sooner do I set my bags down in the Henderson’s beautiful mission owned (and styled) home than we set off for dinner “at a friend’s house.” The friend? Janet Foster, daughter of famed surgeon-statesman-missionary Robert Foster, the man who started all of this. Franklin Graham, son of Billy, director of Samaritan’s Purse, and accomplished philanthropist, says of Robert Foster: “[he] has inspired and challenged me, not only in the ministry with which I’m involved, but also in my personal spiritual journey. When I get to the end of life’s road, I pray that God will have used me even a fraction of the way He has used Bob Foster.”

If one substitutes a surgical dynasty for banking, the Foster’s might as well be the Angolan Medici. On a nearly daily basis, I learn of a new Foster and their enterprises. Most of Robert’s children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews became surgeon missionaries somewhere in Africa, with son Stephen Foster taking up the mantle of CEML. The Fosters have become famous for providing the highest standard of care in Angola, saving lives that would otherwise be a lost cause (often for want of very simple drugs and procedures). When a driver asks my address, I simply say “Stephen Foster’s old house,” and no further questions need answered. If you’re getting hassled by the police, or stopped at a roadblock, merely invoke the name Stephen Foster and barricades part.

Much of the middle class I’ve met in Lubango are somehow involved in one of the various ministries and have formed their own social network. CEML is intimately tied to Serving in Mission (SIM): Angola, as such, the physicians largely socialize with the SIM disciples after work, many of whom (like the Hendersons) also work at the hospital. This relationship has grown to envelope the local pilots for Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) and field operatives for Overland Missions. This has gone so far as to evolve into shared housing compounds, leading to braais (South African BBQ) with aggregations of the most worldly, philanthropic, multi-lingual, globally aware, brilliant and all around interesting people one could ever meet.

Janet Foster, an English teacher and missionary, lives on a property that defies description. Sat alone on a mountainside overlooking Lubango, the home is essentially her lifesize set of Legos. Well-to-do families here often employ locals to do various jobs, when those jobs are finished, they invent new ones. For Janet, this meant two decades of additions to her once humble abode until all children, grandchildren, cousins, and visiting relations have scored their own rooms. The kitchen sprawls out into the courtyard with an absolutely massive outdoor hearth, of her own design and labor (she has these built brick hearths for many friends in the area), upon which she prepared our entire multi-course meal.

At any particular time, myriad languages may be spoken around the dinner table, covering topics from fatalism vs. spiritualism, village outreach to at-risk tribes, new surgical techniques being explored for CEML, or job training projects for local citizens. Sat next to me is Ken Foster, renowned surgeon (of course) who’s filling in for his cousin Stephen from Canada while Stephen is away on one of his ultra remote bush treks. A general surgeon, Ken practiced in Afghanistan from 1997-2011 and is one of only a handful of providers capable of repairing obstetric fistulas (explanation forthcoming). Two Australians, Shannon and Denae, discuss their plan to bring metal fabrication and welding training to Lubango which will create jobs while producing rugged, specialized vehicles akin to those used in the outback. The Hendersons provide dutiful prayers and keep everyone’s cups full; the rest of the table is filled in by various generations of Fosters.

Invariably, as the new “dotour” with CEML, everyone takes a concerted interest in my story, postulating ways to help connect me to someone or something that may help advance my efforts. The hospital’s internist, Dr. Haniel Eller from Brazil, was specifically interested in my plan to develop a clinic in Indonesia which will provide disaster relief in the region. “I know many doctors in that area,” he tells me, “I will put you in touch.” Sure enough, the next morning I wake to WhatsApp messages inviting me to come practice medicine in Java. I’ve traveled with some of the most remote tribes in that country, but I had to come to Africa to connect with Indonesian doctors.

Life is weird. Angola is wonderful.

Are You an Afri-Can? Or an Afri-Can't?

When you’ve been flying for three days straight, have no idea what time zone you’re in, and feel like a sticky hagfish, you just want to grab your luggage, get an ambivalent customs agent, and find the fastest way to a shower before bed. I truly wish I could have had just one of those things.

Unfortunately, I waited around like a jilted lover for the conveyor belt at baggage claim to whir to a stop without ever reciprocating my devotion. Along with a Norwegian punk rock trio who seemed quite comfortable in their stink, I trudged over to the service counter with despair legible on my face. Together we filled out a tome of paperwork describing our luggage, who it was made by, the supply chain logistics that brought it to market, what it’s greatest fears and accomplishments were, and where we could be reached when the airline finally tired of searching for it.

Alright, whatever, I’m in freaking Africa, let’s go adventuring! On my last trip I learned that car rental companies often give much better deals at the counter than they do online in order to try to upsell you. With this in mind I wisely booked a 1.2L VW Polo prior to my departure, fully expecting the counter agent to give me the hardsell on the 4x4 I would actually need to get into the heart of Namibia. I was not, however, expecting the rental car company to have lost all computing power earlier in the day and have my handwritten contract awaiting me with keys at the ready. “No, I’m sorry, sir, we cannot substitute for you today.”

Alright, whatever, I’m in freaking Africa, let’s go adventuring! Tonight’s accommodation had sent me very easy instructions: head into town, go past Independence Ave., turn right at the robot, hotel is on the corner of Bach St. – couldn’t be easier… except, what’s with the robot? Is that a landmark in town? Is it a robotics company? A toy store? Guess I’ll see! Driving into town in my 74 horsepower steed, I’m feeling very proud of my left-handed manual drive muscle memory from my New Zealand days. A short 40-minute jaunt later and I’m in the heart of a tidy central business district with all the modern conveniences. Except where is Independence Ave.? Where are the street signs? Where’s the robot?

Street signs seem to be a thing of the past in this cryptic cyborg metropolis. One could assume the main intersection in town was my transect landmark, so an automaton should reach out at me any second now… Aaaaaany second. A kilometer goes by. Then 5. Then 10. No robots. Nothing even resembling artificial intelligence. No Independence Ave., no Bach Ave. Surely, I missed something, best turn around. All the way back across the other side of town I go, without a single impression of anything on the list of directions.

This goes on for hours until finally I break down and ask a construction worker leaving his site for the day if he had any idea where I was supposed to go. He eagerly climbs in my car and tells me it will be $10 US, a fortune in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fine. Whatever. Get me to a bed!

“Turn right at the roe-bitt” he says in a thick Afrikaans accent, pointing up above to a traffic light. For crying out loud, THAT’S the robot?!

“Where’s Bach Ave?”

“We are on Bach Ave.”

“What? No we’re not, this is Kuaima Riruako Strasse.”

“Yes, same.”

Of course, how silly of me not to have known it was renamed several years ago! I was 2 blocks away the entire time.

Alright, whatever, I’m in freaking Africa, let’s go… to bed… Just one problem: the hotel’s credit card machine is down. “Please, sir, do you have Namibian dollars?” No. I do not have Namibian dollars, and no they will not accept US. Back out into the confusion I go.

OK. I’m done. Let me sleep. No. I’m in a bunk room and there are two people having sex in there right now. Looks like I’m sleeping next to the pool tonight. Happy St. Patrick’s Day to me! :/

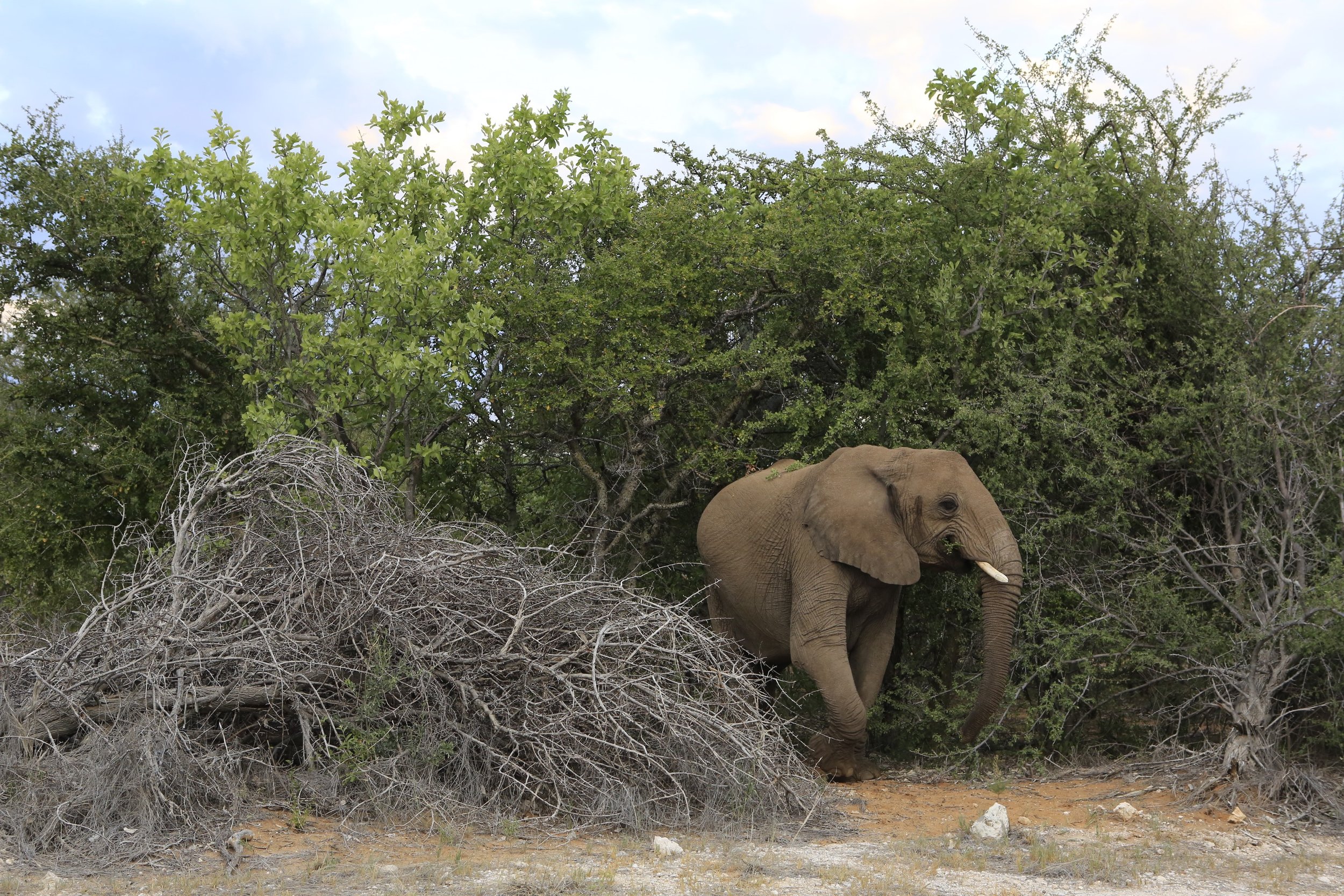

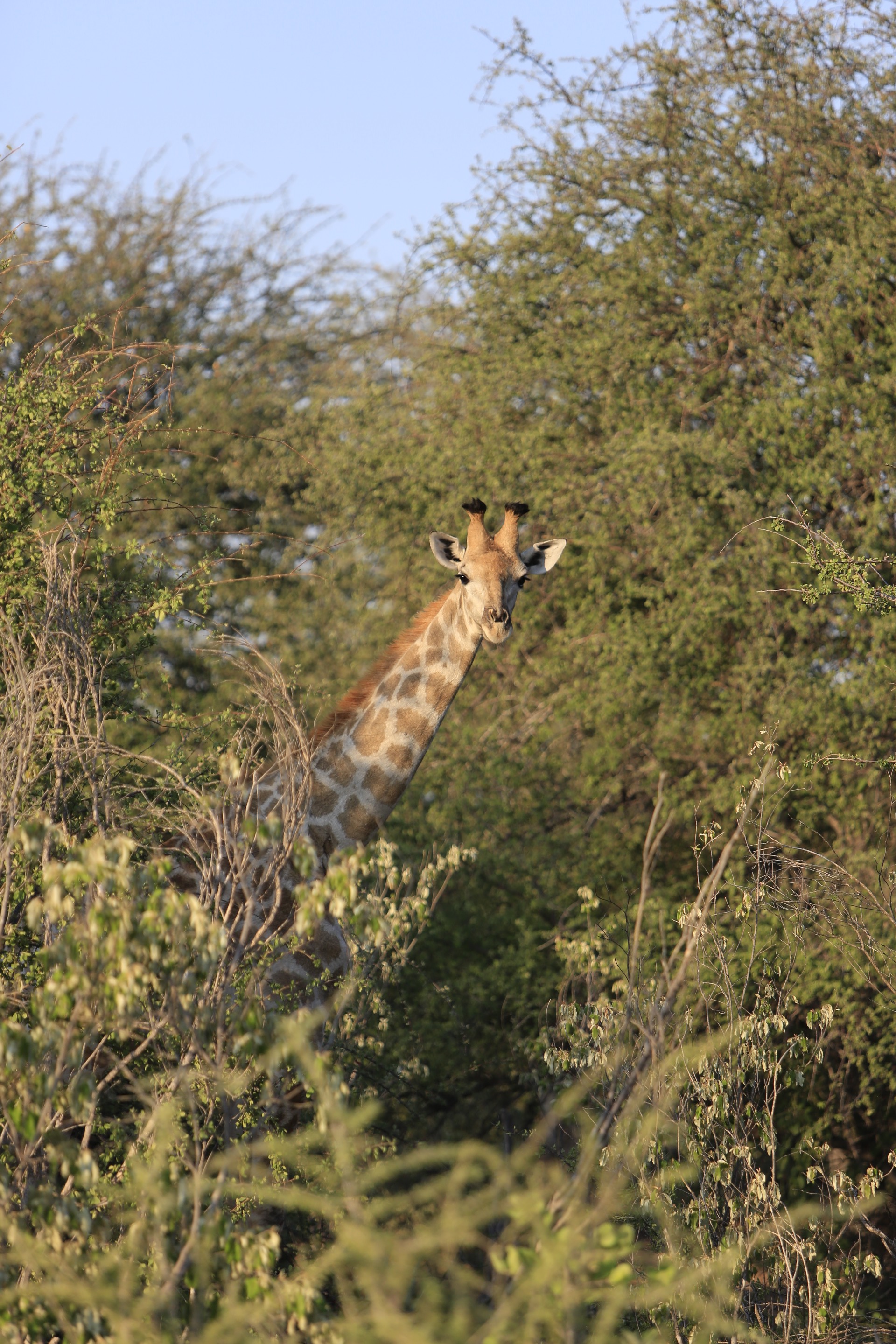

Thoroughly done with Windhoek, I leave at daybreak for Etosha, one of Africa’s crown jewels and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A vast salt pan, Etosha is an unlikely contender for all but the most robust of species to thrive. Nothing could be further from the truth, however, as this remote national park is literally teeming with life. From birds and butterflies, to enormous charismatic megafauna and predators, your field of view is never without spectacle.

Past the guard station at the periphery of the park, I’m immediately greeted by a proud bachelor lion basking in the sunrise like a feline Fabio. On the other side of me is a dazzle (yes, that’s the actual collective noun) of zebra in perfect filiform like tardy businessmen on their morning commute. Up ahead a dark, prodigious shadow lumbers across the road; too big to be a zebra or cat, not tall enough to be an elephant – rhino! A critically endangered black rhinoceros graciously awaits my hesitant approach and allows me a portrait before disappearing into the bush.

I’m roughly 1 mile into the 8,600 square mile park. I haven’t even had my morning coffee yet.

Two days of non-stop, jaw dropping moments pass this way on what is actually nothing more than a stopover precisely in case I missed a flight, or my baggage got lost. The real adventure lies several hundred miles north in Angola, a country which only began offering tourist visas in the Fall of 2018. Two flights per week travel between Windhoek and Lubango, an Angolan city of 2 million people; therefore if I miss that flight I will lose most of a week until making the next one. Since my baggage actually did wind up in limbo, the stopover became invaluable (you hear that, Ohio University? This wasn’t vacation, it was an essential part of the trip’s logistics!).

On the third day I return to Windhoek, still without my luggage or a call answered by the airline in over two days. But beyond all hope, there she is, waiting for me in my bunk, my itinerant duffle had enough of the single life and decided to return to the expedition; and not a moment too soon as I depart in 12 hours! Plus, a change of clothes and a shower would be nice after a week without (and I’m sure my new hosts would appreciate it)!

Getting Ready to Get Ready

Match Week – it’s right up there with graduation as the most exciting rite of medical school. There are many milestones along the way: white coat ceremony is always a tear-jerker, we celebrate being accepted into our program and receive the first totem of our future career; passing boards, placing at our clinical site, and finishing interview season are spectacles to behold if you catch a group of us celebrating together. But above all else, it’s the week we are matched with our future residency program that is singular in its ability to provoke both terror and delight.

For the candidates this means a chance to work with faculty they have always revered or move to their dream town to start a life. Many of us begin the paperwork to finance homes and begin pouring over Zillow with hearts in our eyes. We can move home to be close to the friends and family we’ve been ignoring for the last 4+ years, or to the big city we’ve always seen ourselves in. It is a period of excitement and hope; all things are possible.

It works like this. In the beginning of our 4th year of medical school we begin applying to residencies. They can then decide if they want to invite us to interview, that all sounds normal, right? Well that’s where it all goes terribly awry. Candidates and hospitals court each other for months in what we lovingly refer to as the interview trail; criss-crossing the country in a horribly protracted ballet of who can impress who more without actually seeming overly interested in the other. Programs try to impress candidates with their fitness centers and catered lunches, and candidates flaunt their research credentials like birds of paradise.

You start to recognize candidates from other schools whose interview trail keeps intersecting with yours and greet them as a fellow salty dog. At a certain point you’ve given your elevator speech to so many people and logged so many miles, you wind up reciting the same answers verbatim and have to look at their business card to remember what hospital you’re at. Did I even iron this shirt last night? My tie covers this stain, right?

The months of preening and boasting come down to 5 days in March: Match Week. It can be revelatory, or it can be soul-crushing, for some (like me) it can be both. The stress, worry, and self-doubt are without parallel. As if that weren’t enough, I am one of those attempting to buy my first home - oh yeah, and I’m about to leave for Africa!

Right now, I am sitting in my niece’s Manhattan apartment awaiting my departure. I’ve just accepted the seller’s counter-offer on my dream home (let’s see how the bank feels about all this) and am proud to say I have matched into Internal Medicine at Western Reserve Hospital! I’m going to get to practice medicine in my hometown! …well, after this medical mission to Angola, of course!

First stop: Namibia